Alert

Delaware Supreme Court: Delaware Corporations May Adopt Federal-Forum Provisions Requiring That Securities Act Claims Be Brought Only In Federal Court

Alert

Takeaways

03.24.20

Background

For over 20 years and on multiple fronts, plaintiffs and defendants have battled over where securities class actions and corporate governance claims can, and cannot, be litigated. From the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act of 1998 (SLUSA) to the Delaware Court of Chancery’s Boilermakers decision in 2013[1] to the enactment of Delaware General Corporation Law (DGCL) § 115 in 2015, to the U.S. Supreme Court’s Cyan decision in 2018[2] , each side has won some and lost some. In very broad outline, SLUSA provided that “covered [securities] class actions” must be brought in federal court but its “Delaware carve-out” exempted from this rule most derivative actions and some class actions brought under state law; Boilermakers held that a Delaware corporation could, by bylaw, make Delaware courts the exclusive forum for disputes involving derivative, fiduciary duty, DGCL and internal affairs claims; DGCL § 115 (among other things) codified the result in Boilermakers; and Cyan held that, notwithstanding SLUSA, claims under the Securities Act of 1933 (1933 Act) may be brought in either state or federal court and that, when brought in a state court, cannot be removed to federal court.

The most recent skirmish has been whether, notwithstanding Cyan, a Delaware corporation can require that claims against it and its directors and officers under the 1933 Act be brought only in federal court. In December 2018, the Delaware Court of Chancery said “no.”[3] On March 18, 2020, a unanimous Delaware Supreme Court reversed, saying “yes,” at least to a facial challenge to pre-IPO charter provisions limiting claimants to a federal forum.[4]

Salzberg v. Sciabacucchi—aka The Blue Apron Holdings Case

Before going public, Blue Apron Holdings, Roku and Stitch Fix each added federal forum-selection provisions to their charters. Though the provisions varied slightly (in ways that the Delaware Supreme Court deemed immaterial), each provision more or less said “[u]nless the Company consents in writing to the selection of an alternative forum, the federal district courts of the United States of America shall be the exclusive forum for the resolution of any complaint asserting a cause of action arising under the Securities Act of 1933. Any person or entity purchasing or otherwise acquiring any interest in any security of [the Company] shall be deemed to have notice of and consented to [this provision].”[5]

A stockholder, plaintiff Sciabacucchi, sought a declaratory judgment that the provisions were invalid. Vice Chancellor J. Travis Laster agreed, holding because 1933 Act claims do not “arise out of the corporate contract and do[] not implicate the internal affairs of the corporation” but rather “arise[] from the investor’s purchase of the shares,” the “constitutive documents of a Delaware corporation cannot bind a plaintiff to a particular forum when the claim does not involve rights or relationships that were established by or under Delaware’s corporate law.”[6]

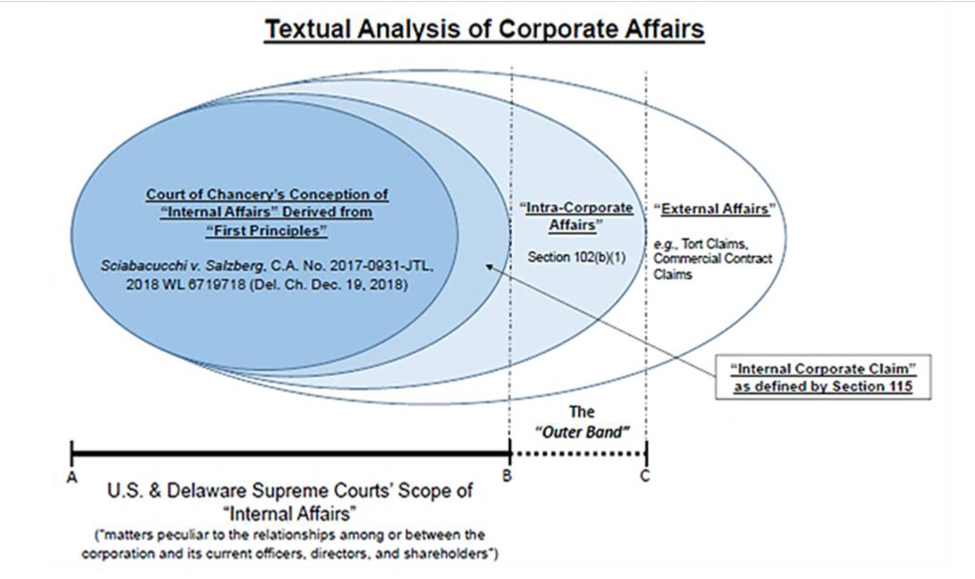

The Supreme Court reversed, holding that such provisions can survive a facial challenge. The Court first held that the federal forum provision was facially valid under DGCL § 102(b)(1), which broadly defines what a corporation’s charter or bylaws can contain. Noting statistics on the number of multi-jurisdictional 1933 Act lawsuits filed since Cyan, the Court suggested that a federal forum provision could be justified on efficiency grounds and would not violate the policies or laws of Delaware, rejected a number of statutory-construction arguments that the 2015 amendments to the DGCL (which had added § 115) had narrowed what § 102(b)(1) permits. The Court then held that § 102(b)(1) is not limited to “internal affairs” matters, disagreeing both with the Vice Chancellor’s limiting construction of “internal affairs” and with the notion that Delaware’s interests went no further than internal affairs properly defined. Illustrating these points with a Venn diagram[7] , the Court instead held that there is an “Outer Band” of “intra-corporate affairs” as to which contractual ordering under § 102(b)(1) also is permissible and that federal forum provisions at least fall within this Outer Band:

The Court held that such provisions do not violate any federal law or policy, noting that the U.S. Supreme Court had decades ago upheld arbitration provisions precluding state court litigation of 1933 Act claims[8] and that both the federal and Delaware approach to forum-selection provisions holds them to be presumptively valid and enforceable.[9] Finally, the Court suggested reasons why its holding should be respected and enforced by Delaware’s sister states—even if federal forum provisions arguably go beyond internal affairs, “[t]he need for uniformity and predictability that [federal forum provisions] address suggest that they fall closer to the ‘internal affairs’ side of the spectrum, which would argue in favor of deference being given to them” and thus “do not violate principles of horizontal sovereignty.”[10]

Take-Aways and Caveats

- Salzberg was a facial challenge; the opinion does not say a federal forum provision will be upheld in every situation. The Court said: “Charter and bylaw provisions that may otherwise be facially valid will not be enforced if adopted or used for an inequitable purpose.”[11]

- The provisions here were in the certificates of incorporation; the stockholders had approved them before the companies went public. While there are good arguments that such provisions would be valid if they were placed in bylaws, had not been approved by the stockholders or were added after an initial public offering, one cannot be sure those arguments will work; language in the opinion stressing the “contractual setting” of these provisions suggests that a provision unilaterally created by a board of directors after a public offering could be viewed differently.[12]

- The provisions here did not attempt to limit which federal courts the stockholder could bring suit in—many 1933 Act actions are brought where the corporation has its principal place of business rather than in Delaware. A provision that attempted to limit stockholders to certain federal courts could be viewed differently.[13]

- This may not be the end of the road: Notwithstanding Rodriguez, the unhappy plaintiff might seek review by the U.S. Supreme Court, which after all decided Cyan unanimously just two years ago.

[1] Boilermakers Local 154 Retirement Fund v. Chevron Corp., 73 A.3d 934 (Del. Ch. 2013).

[2] Cyan, Inc. v. Beaver Cty. Emps. Ret. Fund, 138 S. Ct. 1061 (2018).

[3] Sciabacucchi v. Salzberg, 2018 WL 6719718, at *6 (Del. Ch. Dec. 19, 2018). According to defense counsel, the plaintiff’s name is pronounced “Shaba—Cookie.”

[4] Salzberg v. Sciabacucchi, No. 346, 2019, 2020 WL 1280785 (Del. Mar. 18, 2020). A facial challenge is one that alleges a provision is always unlawful, as opposed to an as-applied challenge, which is one that alleges a provision is unlawful in the particular circumstances in which it is being employed. Plaintiffs make facial challenges when they hope to win on purely legal grounds, without the time and expense of discovery and trial.

[5] Salzberg, slip op. at 7, 2020 WL 1280785, at *3.

[6] Sciabacucchi, 2018 WL 6719718, at *3

[7] Salzberg, slip op. at 41 (the Venn diagram does not appear in the Westlaw version of the opinion).

[8] Salzberg, slip op. at 43, 2020 WL 1280785, at *18-19 (citing Rodriguez de Quijas v. Shearson/American Express, Inc., 490 U.S. 477 (1989)).

[9] Salzberg, slip op. at 44-46, 2020 WL 1280785, at *19-20 (citing M/S Bremen v. Zapata Off-Shore Co., 407 U.S. 1 (1972) and Ingres Corp. v. CA, Inc., 8 A.3d 1143, 1146 (Del. 2010)).

[10] Salzberg, slip op. at 50-52, 2020 WL 1280785, at *23.

[11] Salzberg, slip op. at 49, 2020 WL 1280785, at *21.

[12] Salzberg, slip op. at 48, 2020 WL 1280785, at *21.

[13] Salzberg, slip op. at 51-52, 2020 WL 1280785, at *23.