Alert

Some Copyright Clarity for the Apparel Industry

The Supreme Court provides a test for measuring when graphic features on clothing designs will qualify for copyright protection.

Alert

Takeaways

03.30.17

Last week the Supreme Court articulated a test for the copyrightability of apparel designs. The test does not increase the protection available to the apparel industry, but it does provide clarity for determining when an industrial design will qualify for copyright.

The Court took the case, Star Athletica LLC v. Varsity Brands Inc., to resolve a split in the Circuit Courts regarding what can be called the separability test. To explain what that is, and what the Court decided, some background will help. The basic purpose of Copyright law is to protect an author’s exclusive rights in a work of art created by the author (subject to any assignment or license of protected rights). The term “work of art” is used here broadly to mean all the kinds of creative works, from scientific books to animated cartoons, which Congress has identified as appropriate for copyright protection. To maintain a clear boundary between copyright and patent law, copyright law does not extend protection to things which have utility or practical functionality, because such protection stands in the realm of patent law. The Copyright Act refers to these items as “useful articles,” and examples discussed by the Court are a guitar, a shovel, and a dress. To further clarify the boundary between copyright law and patent law, copyright protection also does not extend to designs of useful articles (i.e., industrial designs).

So far so good in regard to clarity. However, confusion knocks on the door when copyrightable works, such as photographs or drawings, depict useful articles: for example, a painting of a dress would be copyrightable. Confusion opens the door and says hello (as it did to Justice Breyer in his dissenting opinion) when useful articles contain copyrightable works: for example, a dress made of fabric printed with images of roses – the images of the roses would be copyrightable, but not the dress itself (or the fabric). Confusion enters the room and takes a seat when copyrightability is considered for designs of useful articles, such as a dressmaker’s pattern for an evening gown. The Court addresses this most confusing scenario in its opening words. “Congress has provided copyright protection for original works of art, but not for industrial designs,” begins Justice Thomas, before he comments, tersely: “The line between art and industrial design, however, is often difficult to draw.”

The Copyright Act tries to draw that line. One of the categories of protectable works includes pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works. Sometimes a design of a useful article will qualify for this category, and the Copyright Act defines when that happens: “the design of a useful article . . . shall be considered a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work only if, and only to the extent that, such design incorporates pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features that can be identified separately from, and are capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article.” That definition, which introduces the concept of “separability,” has been applied by courts in different ways in different factual contexts.

Separability became contentious in this case, which involved graphic features printed on a Varsity Brands cheerleading uniform. Varsity Brands had registered the copyrights in the graphic features, and when Star Athletica produced a cheerleading uniform with similar features, Varsity Brands sued for copyright infringement. The district court reasoned that the features could not be protected because when the court tried to separate the features from the uniform, they still suggested the uniform, from which the district court concluded that they were utilitarian. Varsity appealed the adverse ruling, and the Sixth Circuit, applying the separability test in a different way, ruled in Varsity’s favor. Star Athletica appealed, and the Supreme Court took the case to settle the separability test.

The Court engaged in straightforward statutory interpretation. Parsing the definition quoted above, Justice Thomas said that a graphic feature in the design of a useful article qualifies for copyright protection “if it (1) can be identified separately from, and (2) is capable of existing independently of the utilitarian aspects of the article.” The tricky part, of course, is the second step, and the Court answered it by saying that the graphic feature qualifies for copyright protection if it “would have been eligible for copyright protection as a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work had it originally been fixed in some tangible medium other than a useful article before being applied to a useful article.” So, in essence, the Court settles the separability test by adding another test question to it: would the graphic feature qualify for copyright protection as a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work if it were fixed in another tangible medium of expression—say, for example, paper? If the answer to that question is yes, then the graphic feature itself is independently copyrightable. In other words, the graphic feature does not lose its protection as copyrightable expression under the Copyright Act simply because it is applied to a useful article that is not copyrightable.

Other than the new alternative medium question, the portion of the opinion which may carry the most impact on the apparel industry is Court’s refutation of the district court’s reasoning. The Supreme Court said the fact that the graphic features on the uniform still suggested the outline of a cheerleader’s uniform when they were separated from the uniform was “not a bar to copyright” because the graphic features would still qualify for copyright protection if they were fixed in another medium. The Court provided another example to illustrate this point: a painting which covers the surface of a guitar. If the painting were separated from the guitar “and placed on an album cover, it would still resemble the shape of the guitar,” but, the Court said, it would not “replicate the guitar as a useful article” because “the design is a two-dimensional work of art that corresponds to the shape of the useful article to which it is applied.” Those words should provide reassurance to the apparel industry that a graphic feature in a design for a useful article of clothing will still be copyrightable even when, if transferred to another medium, it suggests the outline of the article of clothing to which it is applied.

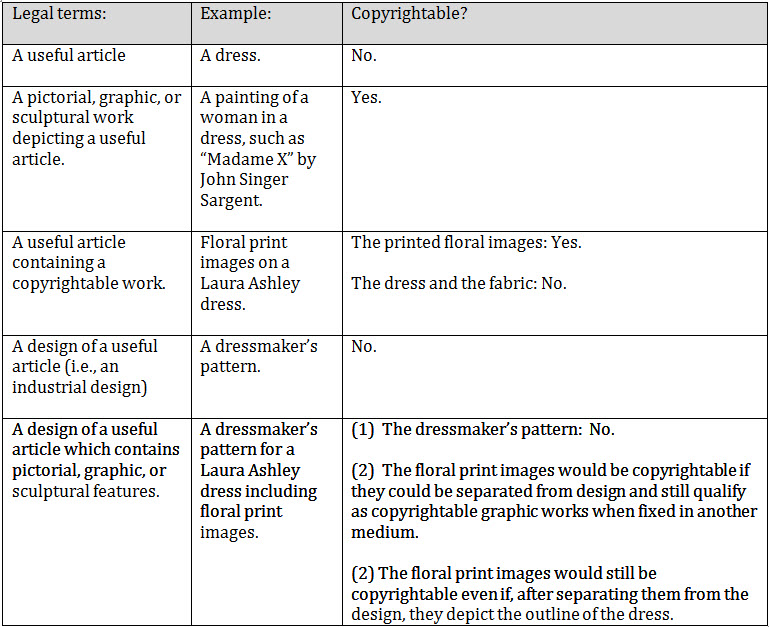

A chart can sum up where the law stands after the Star Athletica decision:

In conclusion, while the test articulated by the Supreme Court appears reasonably clear, its application in practice in the apparel industry, and in other contexts, will evolve as courts struggle with the boundaries of what constitutes a copyrightable work when the work is created solely to enhance a useful article.