Article

Navigating USPTO And Court Standards On Patent Eligibility

Source: Law360

Article

By Eric C. Rusnak,

07.17.20

In April, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office published a report highlighting how the USPTO has brought greater predictability and certainty to the determination of patent eligibility.[1]

This predictability has been a centerpiece of USPTO Director Andrei Iancu's tenure. In response to its release, Iancu stated: "our patent system must move beyond the recent years of confusion and unpredictability on subject matter eligibility. It is now clear that our recent guidelines mark a significant step in that direction."[2]

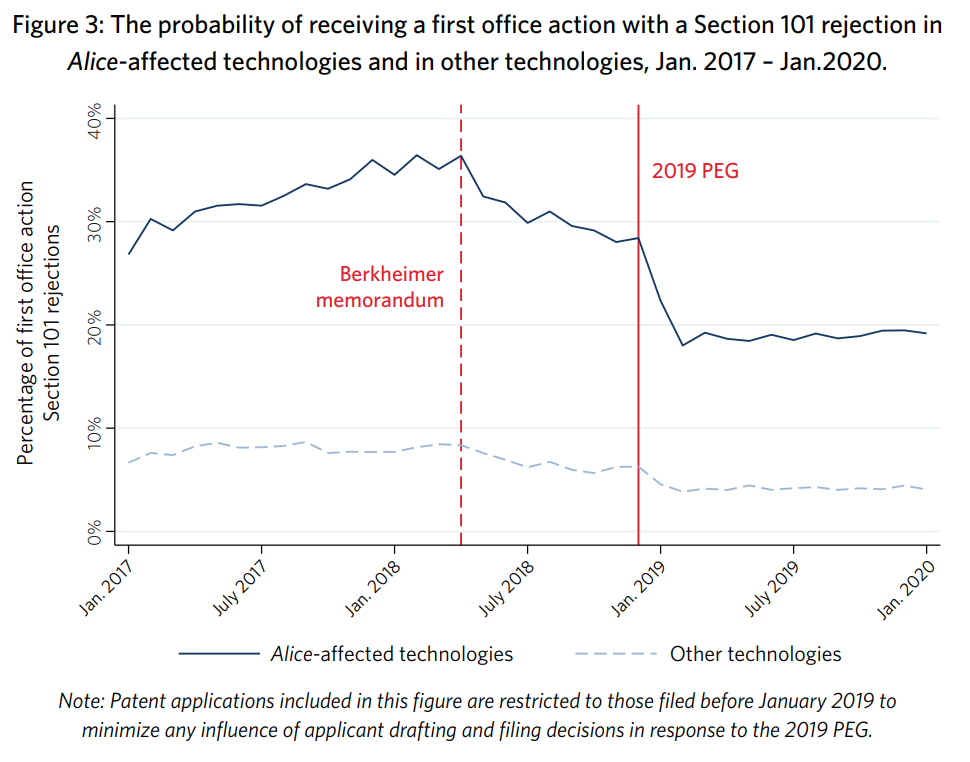

In particular, one of the key findings of the report state that "[u]ncertainty in patent examination for Alice-affected technologies decreased by 44% in 12 months following the issuance of the 2019 PEG."[3]

Figure 3 of the report (shown below) graphically demonstrates the dramatic effect that two USPTO publications, the April 2018 Berkheimer memo[4] and the subsequent 2019 revised patent subject matter eligibility guidance,[5] have had on limiting the Section 101 rejections.

However, since the flatlining of the USPTO's subject matter eligibility rejections under the seminal Alice v. Corp. v. CLS Bank International decision, in early January 2019, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in the nonprecedential opinion Cleveland Clinic Foundation v. True Health Diagnostics LLC stated that it is not bound by the USPTO's guidance in finding a case, seemingly patent eligible under the USPTO's guidance, noneligible. [6]

Overcoming a Section 101 rejection before the USPTO, therefore, does not guarantee success in litigation. In fact, courts are frequently asked to look to patent eligibility at the pleadings stage, irrespective of whether Section 101 was addressed by the USPTO, as defendants move to dismiss patent infringement complaints under Rule 12(b)(6)

The Federal Circuit held in Aatrix Software, Inc. v. Greenshades Software Inc.[7] that patent eligibility can be determined at the Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) state when there are no factual allegations that, taken as true, prevent resolving the eligibility as a matter of law.

The Federal Circuit's 2019 decision in Cellspin Soft Inc. v. Fitbit Inc.[8] provided guidance regarding when a Rule 12(b)(6) dismissal is appropriate, holding that allegations in the complaint that recite a specific, plausible inventive way may be sufficient to defeat a Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss under Section 101.

Under step one of the U.S. Supreme Court's Alice framework,[9] the Federal Circuit held that Cellspin's asserted claims were directed at an abstract idea of capturing and publishing data on one or more websites. But, at Alice step two, the Federal Circuit found that the factual allegations in Cellspin's complaint were sufficient to overcome a motion to dismiss based on Section 101.

Citing the patent claims and specification, Cellspin alleged in its complaint that it was unconventional to separate the capturing and publishing data so that each step would be performed by a different device linked by a wireless connection. The Federal Circuit determined that these factual allegations prevented resolving patent eligibility at the motion to dismiss stage, emphasizing that Cellspin's allegations cited to inventive concepts described in the patent claims.

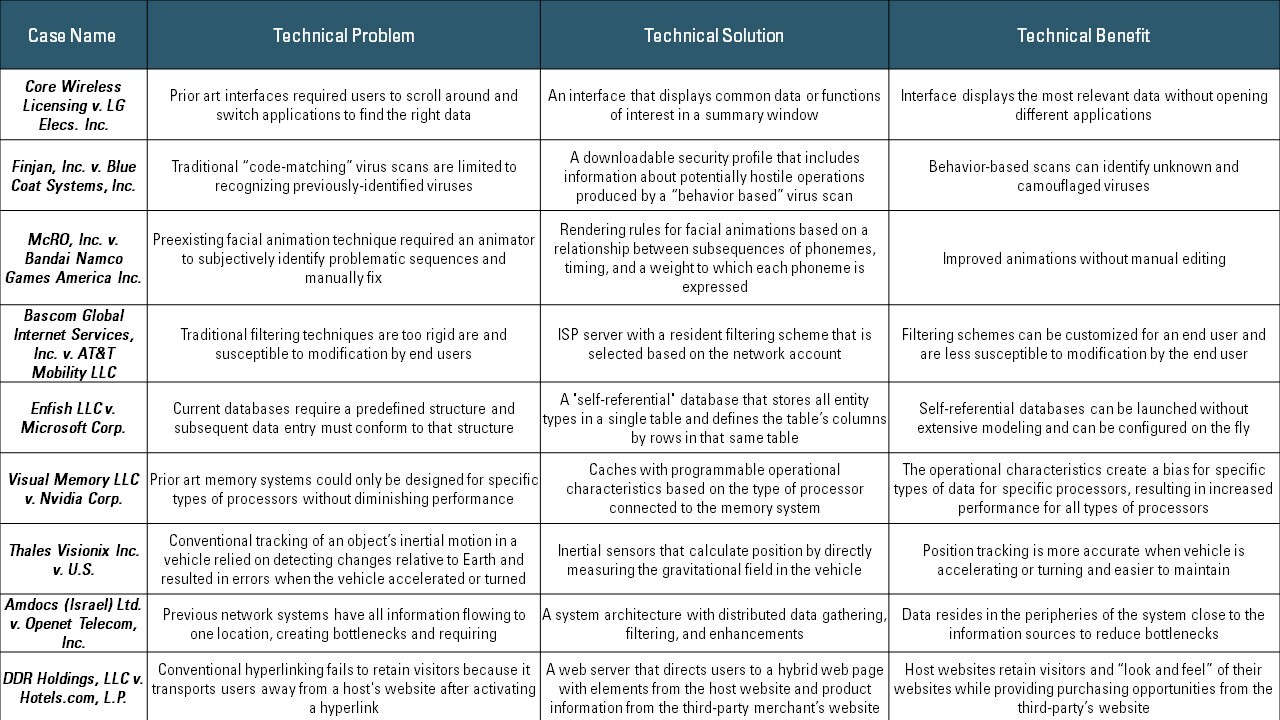

While the USPTO may have provided guidance regarding patent eligibility under Section 101, the courts still do not agree on a bright line test. Nonetheless, when reviewing key court rulings, a pattern emerges of claims being found to contain patent eligible subject matter when the specification and claims clearly recite: (1) a technical problem; (2) a technical solution; and (3) a technical benefit, as shown in the chart below.

That is, the claims recite the technical solution — i.e., the technical features that work to obtain the technical benefit in view of the technical problems — and the specification sells the importance of the technical solution by describing the technical problem and the technical benefit achieved as was described above in Cellspin.

For example, take a hypothetical invention relating to a new phone app for sending text group text messages, but adjusts delivery time for an individual group members time zone. A hypothetical claim for such an invention may look like:

A method of sending text messages using a mobile phone, the method comprising:

- determining, at a mobile phone, a time delay for a message based on a time zone of the recipient;

- delaying, at the mobile phone, the message based on the time delay; and

- sending, by the mobile phone, the message after the delay.

Such a hypothetical claim may even pass muster under the USPTO's guidelines. For example, it is tied to a practical application, e.g., text messaging using a mobile phone, and has an unconventional limitation, e.g., "determining a time delay for the message based on a time zone of the recipient."

However, such a hypothetical claim may face severe challenges in court. How can this claim be improved based on the above pattern and guidance of Cellspin?

First, the claim should be revised to recite the technical solution, i.e., the technical features that work to obtain the technical benefit in view of the technical problems. This is often described as claiming how the invention achieves its benefit.

For example, the hypothetical claim may be revised to describe how the time delay based on the time zone is determined and achieved — i.e., retrieving and comparing the respective time zone identifiers and storing messages in a queue — as shown below:

A method of facilitating improved communications between users using text messages in mobile devices, the method comprising:

- receiving a text message, from a first mobile device, for delivery to a second mobile device;

- retrieving a first time zone identifier corresponding to a current location of the first mobile device and a second time zone identifier corresponding to a current location of the second mobile;

- comparing the first time zone identifier to the second time zone identifier to determine a message delay time for the text message;

- storing the message in a message queue for the message delay time; and

- transmitting the message after the message delay.

But is this enough? Has the specification sold the technical solution by describing the technical problem and the technical benefit? For example, has the specification described that conventional mobile device text messaging systems rely on short message peer-to-peer, or SMPP, protocol, which necessarily sends text messages instantly?

Additionally, has the specification described the technical benefit (i.e., queuing the messages based on delay works around the SMPP protocol)? These benefits do not need to be recited in the claim, but these benefits should be described in the specification to buttress a patent eligibility argument in the USPTO or the courts.

When the specification and claims are drafted in this way, analogizing to the cases in the chart above is simple and navigating the Supreme Court's Alice framework becomes straightforward. For example, the claims are tied to a practical application — i.e., a text messaging application for use in mobile devices using an SMPP protocol — and not an abstract idea; thus, the claims are patentable subject matter under prongs one and two of step 2A.

Additionally, as the claims use unconventional technical features — i.e., retrieving time zone identifiers, comparing to determine a delay, queuing a message based on the delay — the claim is patentable subject matter under step 2B.

In conclusion, by ensuring that your specification and claims clearly recite: (1) a technical problem; (2) a technical solution; and (3) a technical benefit, a patentee may be confident of patent eligibility before both the USPTO and the courts.

[1] Office of the Chief Economist IP Data Highlights, Adjusting to Alice: USPTO patent examination outcomes after Alice Corp v. CLS Bank International, Number 3 (April 2020) available at https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/OCE-DH_AdjustingtoAlice.pdf.

[2] USPTO Press Release (April 23, 2020) available at https://www.uspto.gov/about-us/news-updates/uspto-releases-report-patent-examination-outcomes-after-supreme-courts-alice.

[3] USPTO, supra note 1.

[4] USPTO, "Change in Examination Procedure Pertaining to Subject Matter Eligibility, Recent Subject Matter Eligibility Decision (Berkheimer v. HP, Inc.)" "April 19, 2018) available at https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/memo-berkheimer-20180419.PDF.

[5] USPTO, "The 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance" (January 7, 2019) available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-01-07/pdf/2018-28282.pdf.

[6] Cleveland Clinic Found. v. True Health Diagnostics LLC , 2018-1218 (Fed. Cir. Apr. 1, 2019).

[7] Aatrix Software, Inc. v. Greenshades Software, Inc. , 882 F.3d 1121 (2018).

[8] Cellspin Soft, Inc. v. Fitbit, Inc. , 927 F.3d 1306 (2019).

[9] See Alice Corporation Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank International, et al. , 573 U.S. 208 (June 19, 2014).