Alert

VIE Validity Still Unsure

It may be premature to conclude that the decision of China’s Supreme People’s Court in last year’s Ambow case provides legal cover for variable interest entity structures.

Alert

By Jenny Y. Liu

Takeaways

03.22.17

A 2016 judgment (the “Judgment”) made by the Supreme People’s Court of China (the “Supreme Court”) was believed by some scholars and practitioners to confirm judicial recognition of the VIE structure. We believe the Supreme Court did not go as far as that. On the contrary, the Judgment leaves behind some interesting uncertainties, which might further complicate discussions on the validity of the VIE structure.

I. Facts of the Case and its Judgment

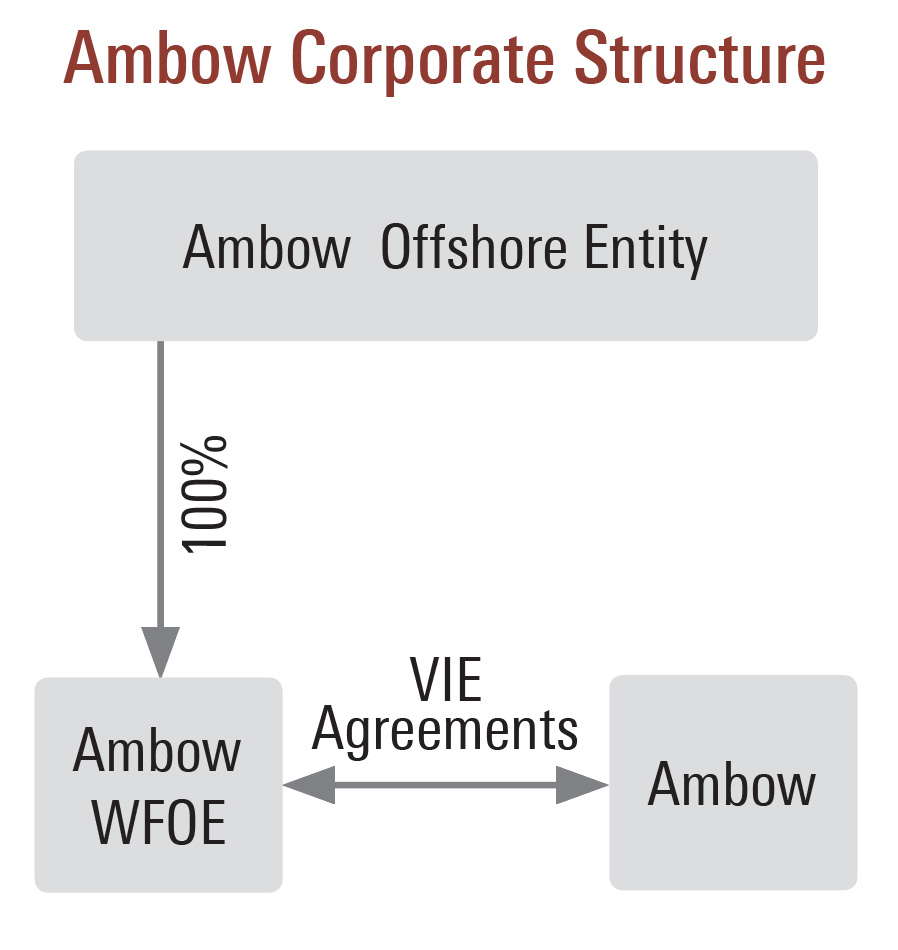

In 2009 Changsha Yaxing Properties Development Co. Ltd. (“Yaxing”) entered into a Framework Agreement (“Framework Agreement”) with Beijing Normal University Ambow Education Technology Co. Ltd. (“Ambow”), under which Yaxing sold to Ambow 70 percent equity interest in two schools (a kindergarten and an elementary school) located in the city of Changsha, Hunan Province. Yaxing later filed a lawsuit against Ambow claiming that the Framework Agreement should be null and void because (a) Ambow, as a VIE entity of Beijing Ambow Online Software Co. Ltd. (“Ambow WFOE”) that is wholly owned by Ambow Education Holding Ltd., a Cayman company, was prohibited from owning controlling interests in education institutions in China in accordance with the Catalogue for the Guidance of Foreign Investment Industries, which provides that foreign investors are prohibited from investing in compulsory education, (b) since Ambow WFOE is not legally permitted to own controlling interest in Chinese education institutions, using Ambow as a “straw” entity to structure around the statutory prohibitions constitutes “deploying legal form to conceal illegal purposes” under PRC Contract Law, which is one of the legal bases to null and void a contract, and (c) allowing Ambow to own controlling interests in schools will harm public interests and education security.

Ambow has entered into a set of standard VIE documents with Ambow WFOE, including (a) a Loan Agreement under which Ambow WFOE lends the money to the shareholders of Ambow for the purpose of making a registered capital contribution into Ambow, (b) an Exclusive Cooperation Agreement, under which Ambow shall pay to Ambow WFOE up to 100 percent of its profits in exchange for the management and consulting services from Ambow WFOE, (c) a Purchase Option Agreement under which Ambow WFOE shall have the right to acquire all of the equity interest held by the existing shareholders of Ambow, and (d) a Proxy, by which the existing shareholders of Ambow granted their shareholders right in Ambow to Ambow WFOE (the Loan Agreement, the Exclusive Cooperation Agreement, the Purchase Option Agreement and the Proxy are collectively referred to as the “VIE Agreements”).

The case was first tried at the Higher People’s Court of Hunan Province, and Yaxing petitioned to the Supreme Court asking it to reverse the decision of the lower court. In its decision, the Supreme Court confirmed the ruling of the Higher People’s Court of Hunan Province. The Supreme Court, in its Judgment, ruled that:

- Ambow is a domestic company, not a foreign invested company. Both shareholders of Ambow are Chinese residents and Ambow is also registered as a domestic company with the local Administration of Industry and Commerce. There is no legal basis to decide otherwise simply because of the fact that the source of the funds for the registered capital contribution is from Ambow WFOE. Also even if the shareholders of Ambow granted their shareholders right to Ambow WFOE under the Proxy, it does not deprive them of their shareholders status in the Ambow and therefore convert Ambow from a domestic company into a foreign invested company.

- Yaxing was fully aware that Ambow is the VIE entity of Ambow WFOE upon signing of the Framework Agreement, and there were no fraudulent or coercive activities of Ambow during the negotiation and execution of the Framework Agreement. Hence the Framework Agreement reflects the true intention of the parties and cannot be voided because of fraud and/or coercion.

- Neither can the Framework Agreement be voided based on violation of mandatory legal requirements under PRC law. PRC Contract Law provides that “a contract can be voided if it violates mandatory requirements under laws and regulations.” The Supreme Court alleges that the “laws and regulations” referred to therein shall be the laws and regulations published by the Congress (including its Standing Committee) and the State Council, not the local or other administrative rules. The legal prohibitions cited by Yaxing are mainly provided under the Catalogue for the Guidance of Foreign Investment Industries (which is promulgated by the National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Commerce) and the Security Inspection Rules for Acquisition of Domestic Companies by Foreign Investors (which is promulgated by the Ministry of Commerce) and therefore shall not be considered as the “mandatory requirements under laws and regulations” for the purpose of voiding a contract.

- Whether the de facto acquisition of controlling interest in schools by Ambow WFOE through its VIE entity in China constitutes a violation of the prohibitions under the Regulation on Sino-Foreign Cooperative Education (“Cooperative Education Regulation”, which is promulgated by the State Council), the Supreme Court deferred to the Ministry of Education of PRC (“MOE”), who opined that the controlling right granted to a foreign investor under its contractual arrangement with the shareholders of a domestic education entity shall not be considered as direct involvement in the operation and management of such domestic education entity and therefore such contractual arrangement is not subject to the Cooperative Education Regulation.

- The sale and transfer of equity interest from Yaxing to Ambow has been properly registered with competent government authority, and there is no evidence that Ambow and the schools it controls have conducted any illegal activities since then. Therefore the claim of Yaxing that ownership of Ambow in the schools will harm public interest and education security has no factual support and legal basis.

The Supreme Court, however, did urge the MOE and its local branches to scrutinize their review and supervision of activities that might involve de facto control of education institutions by foreign investors and suggested the education administration authorities regulate and even punish such activities under the framework of administrative rules and administrative enforcement actions.

II. Our Observations

Although the Supreme Court did not void the Framework Agreement, we do not believe the Judgment signaled judicial recognition of the VIE structure, as some scholars and practitioners would like to believe.

First, the Judgment expressly limits its ruling on the validity of the Framework Agreement, bases its analyses on contract law principles and doctrines, and specifically avoids making any decision on the legitimacy of the VIE structure and the validity of the VIE Agreements. Under the Judgment, the Supreme Court states that, “the validity of the VIE Agreements are not disputed between Yaxing and Ambow and therefore will not be decided by this court.”

Secondly, although the Supreme Court defers to the MOE as to whether the de facto control by a foreign investor of the education institutions shall be considered as a violation of mandatory requirements under the Cooperative Education Regulation and therefore provides the legal basis to void the Framework Agreement, the Supreme Court issued a Judicial Opinion to the MOE, suggesting the latter to take concrete measures to regulate same or similar situation and to punish any illegal activities through administrative enforcement. The language of the Judgment, based on our reading between the lines, implies that the Supreme Court did not rule on the issues involving the VIE structure only because the VIE Agreements are not the subject of disputes between Yaxing and Ambow, and it does not necessarily mean that the Supreme Court recognizes the validity of the VIE Agreement—“I don’t like it, but my hands are tied.”

Third, the prohibitions under the Catalogue for the Guidance of Foreign Investment Industries, which is promulgated by the National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Commerce, cannot be used as legal basis for voiding a contract due to violation of mandatory legal requirements. However, considering that the Catalogue for the Guidance of Foreign Investment Industries will gradually be replaced with the Market Entry Negative List, which is the direct administrative legislation product of the State Council and provides same or similar foreign investment restrictions and prohibitions as the Catalogue for the Guidance of Foreign Investment Industries, the Supreme Court will gain access to the tools needed to void a contract involving VIE structure.

Those being said, the Judgment does leave behind some interesting uncertainties, which might further complicate discussions on the validity of VIE structure. For example, if the case is between two companies in the Internet industry where VIE structures are also commonly used, will the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (“MIIT”) decide the same as the MOE that no violation of any mandatory legal requirements occurred? And if the MIIT makes a negative decision, will it affect the ruling of the Supreme Court? It is also interesting to see whether the MOE will follow the suggestions made under the Judicial Opinion and take any measures to tighten the loose ends involving de facto foreign control over Chinese education institutions.

It is especially important to note that China does not adopt common law system, and therefore judgments made by the Supreme Court are not required to be followed by other courts or even the Supreme Court itself in other cases involving the same or similar facts patterns.